In the great commons at Gaia’s Landing we have a tall and particularly beautiful stand of white pine, planted at the time of the first colonies. It represents our promise to the people, and to Planet itself, never to repeat the tragedy of Earth.

—Lady Deirdre Skye, “Planet Dreams”

Alpha Centauri is one of those singularly arresting games which has forever refused to let me go. It lives in my brain somewhere, or maybe my soul, like a slithering conceptual worm: so that every time something strikes a certain chord, or approaches a certain intensity, I think of Lady Deirdre Skye, and the Planet Dreams, and Our Secret War, and the sky — the real sky, up above — seems a little more strange, and sullen, and beautiful. Although it is profoundly flawed, Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri (henceforth SMAC) is one of the only computer games one can reasonably approach as gestalt ‘major’ work. It’s a totally sincere, and totally committed to a certain tracing-out of the world as it exists, in full fidelity, across every domain of experience. That’s a rare and precious thing; I’d like to do something with it.

With this series — this long, long series — I’d like to encourage some thoughtful collaboration. In each post I’ll play a little bit of SMAC, until our nascent civilization acquires a new technology. Then, we’ll interrogate that technology, and the figurative mechanics the game uses to depict it. We’ll be pairing each technology with an interesting but basically B-list book or monograph on some relevant theoretical problems in philosophy, technology, science, economics, engineering, &c. using SMAC to ‘think through’ some other complex of ideas. If the subject is especially technical, I’ll also suggest a textbook or paper. By the end of the tech tree, we’ll have constructed some novel, sophisticated assemblage, cobbled together from books and rules and models: a little thinking machine, to trace out certain lines of flight, arcing away from Alpha Centauri and the intersteller-Y2K it figures.

Ideally, this isn’t just a monologue. There are 78 technologies in SMAC; that’s a hell of a lot of books. If you’d like to follow along, or suggest a book pairing, I’d be very excited to have you. I fully intend for this to be a ‘Let’s Play’ in the old Something Awful mode — collaborative and inter-textual. Reply in the comments, or on Twitter, Bluesky, &c. This ‘Let’s Play & Read’ is going to take years. We’ve plenty of time to figure things out: to design own peculiar University of Planet.

First, a summary. Alpha Centauri is a 4X empire-builder in the mold of Civilization. Essentially a space opera, the game is nonetheless credibly disguised as hard science fiction. Our little pixel people are the last survivors of the doomed U.N. Unity mission — a kind of cryosleep ark-ship sent off to Sol’s closest neighbor-star so that some might survive the coming global war. Awakening early to find the Unity in an irreversible process of rapid, asteroid-induced disassembly, the would-be colonists struggle for control of their beleaguered ship. Politically disorganized, practically overcome, and totally unable to contact Earth, fragments of the surviving crew head for separate escape pods. Global Unity gives way to ideological tribalism; in just a few days, Earth’s forlorn hope has reproduced all the problems of its home star.

We’ll be playing as Lady Deirdre Skye, the Unity’s Chief Botanist and Xenobiologist. A Scottish Cornell graduate renowned for her work on genetically modified crops, Deirdre Skye is one of SMAC’s most curious characters. From a certain angle, she recalls Ada Lovelace: approaching the literary-symbolic and the scientific as interconnected sister-fields, Skye spends much of the game developing a ‘poetical science’ of Planetary ecology. During the Unity’s terminal crisis, she is a preeminent figure in the crew’s ecological intelligentsia, and leads an informal group down the surface in an escape pod. With this preliminary cadre, she establishes the new world’s first ideologically coherent faction: Gaia’s Stepdaughters.

Arriving scattered across the surface of Planet, each bloc starts the game with distinct values and aspirations — modeled by the game’s Social Engineering system. The Gaians, for instance, enter play with +1 Planet Score for their “environmental safeguards”, and +2 Efficiency for their “experience with life systems & recycling”. In exchange, they suffer -1 Morale for their “pacifist tendencies”, and -1 Police for their relative libertarianism (Manual p. 124). As our society evolves, we will slowly modify this baseline disposition, adopting new systems of economics, valuation, and political organization. Such Social Engineering choices will slowly transform our society, and ultimately prefigure the most important choice of all: the selection and development of a Future Society for our citizens. There are certain synergies along the way, but very little (except the ironclad Gaian aversion to Free Market economics) is really set in stone. As we develop our newborn society, we will therefore have to respond dynamically to our habitat.

To mediate that initial encounter with the conditions on Planet, each faction also receives a distinct starting technology. As the Gaians, we start with Centauri Ecology: the nascent study of Planet’s natural environment. That’s the primary subject of our post today. Quoting here from the associated in-game datalinks:

Planet’s atmosphere, though a gasping death to humans and most animals, is paradise for Earth plants. The high nitrate content of the soil and the rich yellow sunlight bring an abundant harvest wherever adjustments can be made for the unusual soil conditions.

—Lady Deirdre Skye, “A Comparative Biology of Planet”

The bit about nitrates isn’t just a bluff: on the old Alpha Centauri website (and in the supplementary GURPS book, which is an odd beast — something we’ll return to later) the game’s design team published a wealth of supplementary information. We know, for example, Planet’s precise weight in kilograms (1.10E+25) and atmospheric pressure (1.74 bar). We also have a sense for the composition of Planet’s atmosphere: 90.90% nitrogen and 8.52% oxygen (compared to Earth’s 78.09% N and 20.95% O). We cannot ‘solve’ for soil composition from such information alone, but we can speculate a little. Nitrates are biologically (bacterially) produced by a complex series of aerobic and anaerobic transformations (nitrogen fixation → nitritation → nitrite oxidation). Such process are fundamental to life, and tend to occur with greater frequency in environments with a surplus of nitrogen — eutrophic lakes, for example. Since Planet has a robust fungal (quasi-fungal?) ecology, we would expect it to have some similar organisms (quasi-bacteria?) performing a similar role. A modest but noticeable increase in surface nitrates therefore seems totally plausible to my untrained eye, well explained by the surplus of atmospheric nitrogen

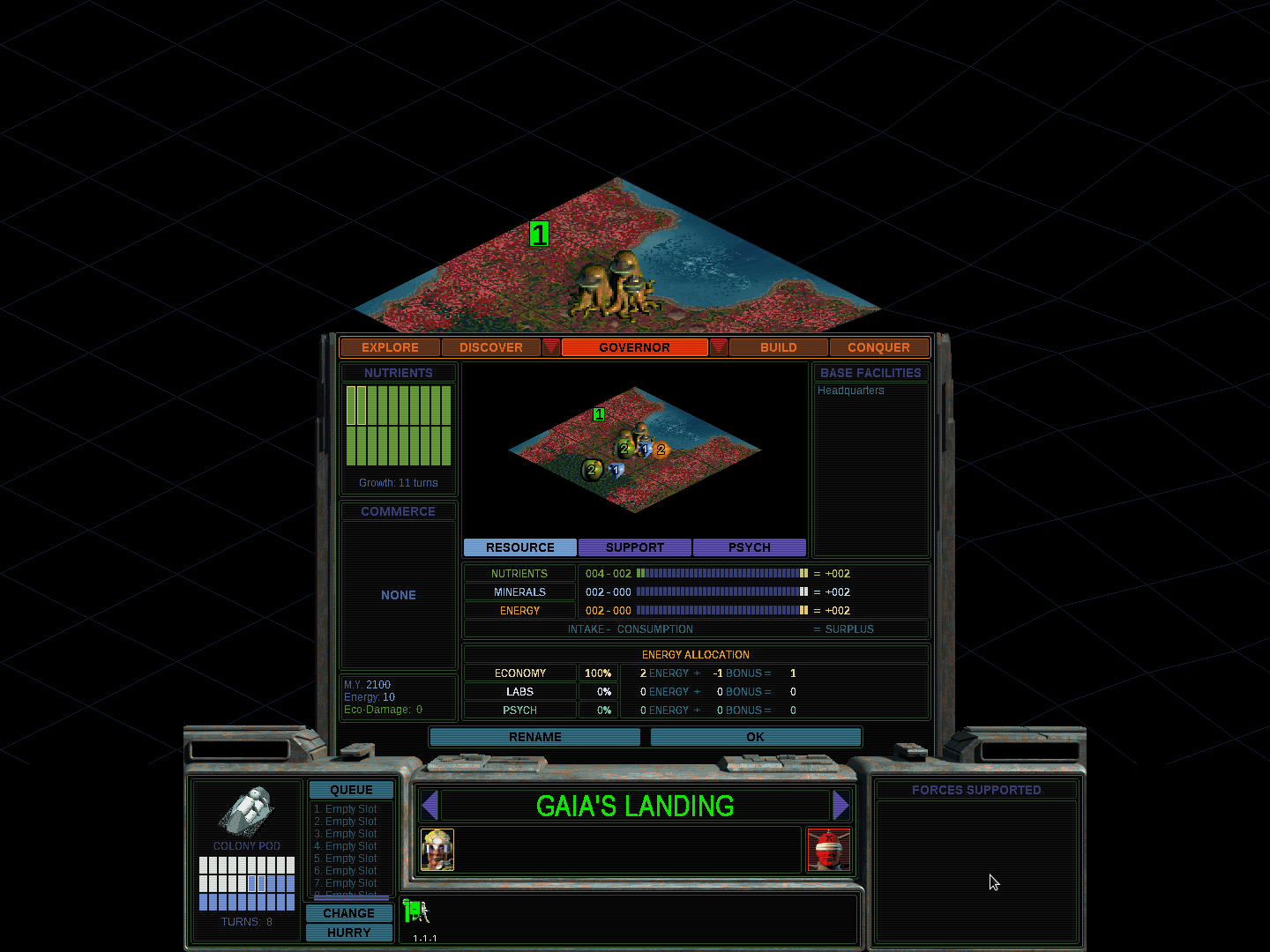

There are more details in the GURPs book, but we needn’t get into them here. I’m really trying to impress the principle: there is a profound and peculiar ‘grounding’ effect at work here. Consider our starting position, above. That’s our colony pod, in the middle. To the south-west, we can see the edge of Planet’s only natural rain forest: the Monsoon Jungle, “an anomalous expanse of thick and curiously earthlike vegetation” (Manual p. 44). On Earth, the soil in rainforests is usually quite poor and depleted. Not so, on Planet. According to the manual, “The rich soil of the Monsoon Jungle yields +1 nutrient per square” (p. 44). The closest Earth analogue is Amazonian Terra Preta, but that soil was created by anthropogenic charcoal deposition. What exactly happened here? Volcanic activity? Space aliens? We’ll return to such questions later, but for now, the answer less important than the effect. With just a few ‘fixed’ details corresponding in a coherent way to real, physical constraints, notice how readily we can begin to theorize; nestled between realistic values, even apparent irregularities invite us to imagine speculative ecologies.

Remarkably, such ecologies are describing something genuinely ecological. Unlike most computer games, Alpha Centauri’s landscape responds dynamically to changing conditions. West-facing slopes receive a greater quantity of rainfall (for instance), while east-facing slopes dry out. Since resource yields are calculated dynamically according to moisture levels, a player can use this dynamic to her advantage. She could (for example) send terraforming teams to the eastern edge of her empire, to raise a borderland mountain ridge. Her lands would become more agriculturally productive, and the foreign land to the east would dry out or go fallow. This is obviously an imperfect simplification of real climate models, which are hideously complex and multifaceted. Nonetheless, it’s enough to force us to carefully consider the game map. This map is not really a map, but rather, an environment: an interactive plane of intensities, which cannot be reduced to a static image. It adapts and responds to our activities. This is especially true of the red xenofungus surrounding our base — but that’s a story for another post.

Presently following these lines of ecological inquiry, I’d like to introduce Félix Guattari’s The Three Ecologies as our first critical text — for I think it well establishes our project. Starting from the beginning:

The Earth is undergoing a period of intense techno-scientific transformations. If no remedy is found, the ecological disequilibrium this has generated will ultimately threaten the continuation of life on the planet's surface. Alongside these upheavals, human modes of life, both individual and collective are progressively deteriorating. Kinship networks tend to be reduced to a bare minimum; domestic life is being poisoned by the gangrene of mass-media consumption; family and married life are frequently 'ossified' by a sort of standardization of behaviour; and neighbourhood relations are generally reduced to their meanest expression. . .

— Félix Guattari, The Three Ecologies, p. 27.

Guattari was a clinical psychologist of unusual pedigree. Trained under preeminent French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, one might have expected him to become a Freudian par excellence. On the contrary, Guattari spent decades at the experimental clinic La Borde, which specialized in the democratic treatment of psychotics. Here, he broke with the Freudian Oedipal model. With his fellow clinicians, he pioneered schizoanalysis — a psychodynamic practice which tries to show how “desire might come to desire it’s own repression” and produce the kind of radical repressive terror evident in an extreme form in the clinical schizophrenic, without reducing the individual to a grand theory of primary traumas (Deleuze & Guattari p. 105). Shizophrenia, in the schizoanlytic model, arises out of a dysfunctional constellation of social and psychological factors, which put the schizophrenic in a state of extreme precarity. She is forced to distinguish her desires from herself so that she might hide or destroy them — and in fact, might come to desire this destruction, insofar as it affords her a kind of safety or security. Hence, La Borde: a chateau-hospital at a pleasant French farm, with clinicians, and forests, and Shakespeare, treating schizophrenics with adaptive, low-stakes social integration, and a dynamic incitement to engage in creative self expression (perhaps acting, painting, &c). An evolving multi-domain solution, for an equally complex problem.

In The Three Ecologies, Guattari works along these lines, dealing with likewise-complex problems of social organization and political economy. He suggests we move away from strictly delineated fields and ideal solutions, instead learning to engage with problems of the eponymous three ecologies — “the environment, social relations and human subjectivity” — experimentally, in tandem (p. 28). Maybe more precisely, he thinks we’re going to have to. “Of course”, he concedes, “such a substitution will not be automatic. But it nevertheless appears probable that these issues, which correspond to an extreme complexification of social, economic and international contexts, will increasingly come to the foreground” (p. 30). Otherwise, “we can unfortunately predict the rise of all kinds of danger: racism, religious fanaticism, nationalitary schisms that suddenly flip into reactionary closure, the exploitation of child labour, the oppression of women…” (p. 35). The problems of the modern world exist across domains, in a complex pattern of development over time: we cannot get a handle on them working one angle at a time.

The Three Ecologies was written in 1989, and is largely considered with issues of that historical moment (globalization, the collapse of the eastern bloc, the apparent ‘end of history’, &c). For our project of speculative imagination, these problems are besides the point. What we’re really interested in is the method, especially this notion of ‘ecology’, applied homologously to the social and psychological field. Recall that ecology is foundationally the study of natural relations, and the patterns which govern the circulation of certain critical qualities in nature: the circulation of energy, of biomass, of population, and so forth. It is easy to see how we might apply this to the social field, and think in terms of a ‘human ecology’ of interrelated institutions, tendencies, formations, &c. It is harder to see how it applies to the mind, for we tend to think of the mind as a kind of Cartesian ego or subject: we imagine ourselves in the singular, and consider any profound disjunction or rupture (schizo-whatever) in terms of disorder or dysfunction.

Yet, as Guattari points out, we should not take this process of ‘subjectification’ for granted: for “interiority establishes itself at the crossroads of multiple components, each relatively autonomous in relation to the other, and, if need be, in open conflict” — a bubbling morass, constantly reconfigured by the contradictory demands of (conflicting) socializations, inheritances, drives, &c (p. 36). The schizophrenic is not the only one with a multiplicity of competing desires. Each of us is several, arising out of various encounters and apperceptions, only thereafter constructed in our interactions (with ourselves, with nature, with others) into the coherent entity we recognize with ‘I’ or ‘you’. The subject is built, formed according to some mold; moreover, it is constantly at risk of de- or re- forming under pressure from social, environmental, and internal-psychological drives. We exist in a kind of psychic homeostasis, remaking ourselves to suit (and work with) the world.

The fundamental insight here, for our purposes: the three ecologies are actually mutually reinforcing, and in some formal sense indistinguishable. Just as much as the (e.g.) the social field depends on the environment it exists in, and in fact shapes and constructs that environment over time — likewise, the social and environmental fields shape the psychological. Our mind is built up in relation to the peculiar conditions that surround it, which we grow up relating to, and constantly reinforce. There is no ‘initial self’, nor is there some ‘true self’ hiding underneath the morass. Rather, there are manifold desires, changing all the time to meet the ecological demands of the world around us — and vice versa. Psychopolitical ideology therefore follows ecology, and is in a very real sense part of the ecological environment. Our world gives us the sort of mind which wants to make more worlds like this one: our habits and patterns of suppression subjectify us, leaving us at a certain distance from the world outside.

This process is not useless or strictly speaking ‘bad’ — for otherwise, we all be clinical psychotics. Still, it is awfully stiffing. Where we might have perceived certain possibilities, certain risks worth taking, we instead fixate on symbols, identities, metaphors, and other ideal psychological objects. We tend towards the over-determined, and the archaic.

How can we get out of this terrible bind? “The unconscious remains bound to archaic fixations only as long as there is no investment […] directing it towards the future”, writes Guattari (p. 38); but escape is trickier than it might seem, for “post-industrial capitalism […] tends increasingly to decentre its sites of power, moving away from structures producing goods and services towards structures producing signs, syntax and - in particular, through the control which it exercises over the media, advertising, opinion polls, etc. — [i.e.] subjectivity” in its own mode (p. 47). Modernity, in other words, is terrified of ‘going all the way’. The capitalist transmutation of all value into the money-form is in principle abstracting (contrast e.g. the ‘special’ values of noble blood, lineage, &c. in the medieval order, irreducible to money). Nonetheless, at the last moment, capital tends to pull-back: to cancel the future. It invests tremendous energy into a regime of discipline and control which can only ever hope to stifle or complicate the free flow of abstract value.

This apparent paradox is really not so confusing. In a regime of totally abstract value, the systems of subjective discipline that make modern capitalism possible (police authority and criminal law, for example) would disappear, replaced by some new dynamic. Whether this new dynamic would be better or worse is not really the point: in either case, it would signal the end of international capitalism. The forces which have benefited most from any (!) presently-extant ecological situation — the forces which therefore dominate that ecology — will generally resist such self-obliteration. It is precisely this resistance which produces the predominant pychopolitical problems of power and possibility, which is to say, ideology.

To chart new paths, we therefore need forms of speculative cartography: maps of minds, planets, and societies, with all the exits marked. Insofar as we are subjectified, our psychic ecology is the most difficult to perceive. It thus frequently become the last redoubt of the old regime, from which it might assert itself (through us, through all of us) back on to the biosocial order — not as some kind of alien parasite, but because the current world is what we have come to sincerely desire. To escape, we do not merely need to make a change. Rather, we need to produce the kind of psychological rupture that makes change seem desirable. Such rupture is the work of art, emerging from the complex circulation of intersubjectivies pushed to the point of incoherence. After all, “are not the best cartographies of the psyche, or, if you like, the best psychoanalyses, those of Goethe, Proust, Joyce, Artaud and Beckett, rather than Freud, Jung and Lacan?” (p. 37). With art and playful speculation, we can pick apart our subjectivity into its constituent drives, and learn how to desire something different — how to desire a new world worth making.

Working along these lines, I suggest that we first approach Alpha Centauri as an ecological imagining-machine. As Guattari and Gilles Deleuze write in 1972’s Anti-Oedipus, “an author is great because he cannot prevent himself from tracing flows and causing them to circulate, flows that split asunder the catholic and despotic signifier of his work, and that necessarily nourish a revolutionary machine on the horizon” (p. 133). We might therefore read the game like a writer reads the news; moreover, use the game like writer uses her pen. There are plenty of ‘flows’ to trace out, or instigate — and myriad futures loom on the horizon.

For the first few decades, we will be concerned with very elementary flows, and rather prosaic futures: flows of food, water, power, iron, nitrates, &c. Per the datalinks, “finding adequate sources of nutrients, energy, and minerals is the most immediate problem facing the colonists after Planetfall”. With “Centauri Ecology”, our starting technology, our colonists avail themselves of “the tools they need to begin shaping the world around them” discovering “how plants grow, what geological structures exist, and how natural energy sources may be exploited on Planet”. Presumably, our Gaian intellectuals are well-primed for such problems, and resolve them in the first few fleeting weeks and months.

Even at this primitive stage, things are awfully complex. Notice that the ‘social engineering’ system immediately imposes itself on our relationship with the natural environment. From Gaia’s Landing, we can initially send our citizens to work on any one of the surrounding tiles. As the inflow of nutrients lets us grow our population, we will be able to work more — but we’re almost totally surrounded by low-utility xenofungus. Moreover, our low Social Engineering Police score will make it hard to keep control of our base if it grows too big. We are therefore loosely incentivized to expand, and focus our early efforts on the creation of a second base in the nutrient rich Monsoon Jungle. Right from the beginning, we are dealing with dynamic ecological systems, which cannot really be described as problems which singularly belong to one field or the other. Our problems span multiple domains.

Over the next four-hundred mission years, our imaginary society will figure a multiplicity of such systems, and deal with innumerable problems. Out of our environment a particular social field will emerge: not just in the Social Engineering system, but also in the whole multiplicity of interrelated productive organs that together constitute our developing civilization. Every building, every worker-placement, exists in a straightforwardly described but altogether hideously complex (i.e. basically ‘unsolvable’) relationship with the environment of Planet. We will naturally focus on the projects are most productive in the particular conditions of our initial environment; then, we shall adopt the social policy that makes those products most effective. Such policies will produce new innovations, economies, technologies, &c. — varied transformations, altogether reconfiguring the environment that grounds them, with imperfect cyclicity.

As this integrated ‘system of relations’ develops, it will likewise naturally present certain questions of psychic ecology: a whole new world of competing drives and desires. Gradually, we will turn towards the critical questions the game’s Social Engineering system describes in terms of Future Society — questions Guattari might have described in terms of ‘subjectification’. What sort of person might we start becoming, to make a future society worth wanting: a society which is flexible, and open to a certain kinds of risk? What sort of future might our emerging ecology produce? These questions cannot be productively approached a priori or resolved with some perfect calculation. Rather, they are best understood with dynamic experimentation: for we are here working in terms of virtual futures, trying to discover certain “desiring-machines on the horizon” (Deleuze & Guattari p. 369), tracing out lines of escape. We therefore proceed in the spirit of playful exploration, and watch as our speculative world begins to imagine itself.

High above Planet, the twin suns circulate in consonance. Below, in the double shadow of an escape-pod colossus, mask-clad acolytes haul makeshift iron tools down to the nutrient valley. Daylight is breaking on the surface of the deep.

Deleuze, Gilles & Félix Guattari. Anti-Oedipus. Trans. Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane. ISBN: 0816612250

Guattari, Félix. The Three Ecologies. Trans. Ian Pindar and Paul Sutton. ISBN: 0485004089

Zeigler, Jon F. GURPS: Alpha Centauri. ISBN: 9781556345203

This is awesome; I'm very excited for this series. SMAC is my favorite game and I may have quoted Deirdre Skye in my philosophy thesis. I'll be looking forward to the duel of ideas with Chairman Yang - but for the moment, it seems I've got to brush up on my D&G.